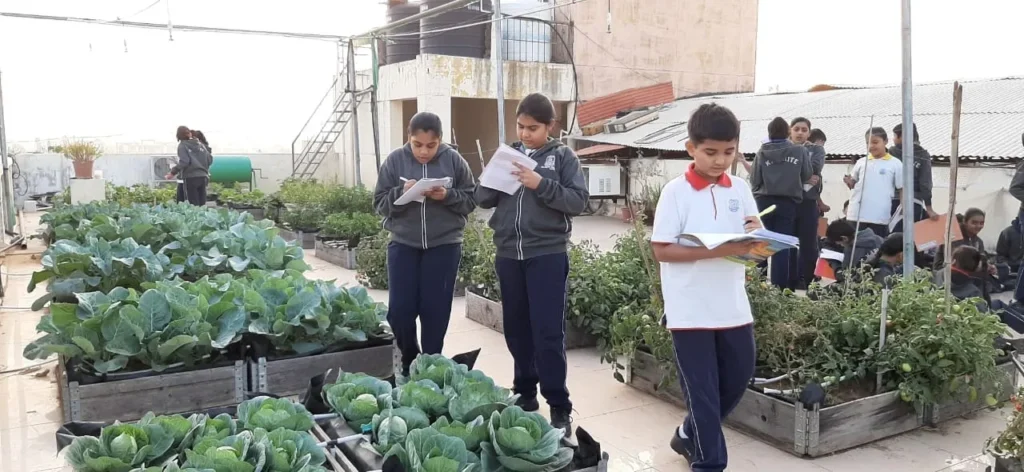

When an unexpected October downpour flattened a thriving cabbage patch in a Vadodara school, a group of children stood silently, watching their weeks of effort disappear. Some even cried. For Hitarth Pandya, their mentor, that moment was powerful proof that his experiment was working: empathy, resilience, and awareness had been planted far deeper than the seeds themselves.

This is the story of how a former journalist traded breaking news for breaking soil, and in the process, nurtured over 20,000 young environmentalists across five Vadodara schools.

The Journalist Who Walked Away

For nearly a decade, Pandya worked in the newsrooms of The Times of India, The Indian Express, and Divya Bhaskar. His bylines highlighted deforestation, vanishing wetlands, and farmer distress. But one question haunted him: Did these stories change anything?

“The turning point was in 2012,” he recalls. “By 2015, I quit journalism. I wanted impact, not just headlines.”

His answer was children. Instead of reporting about a broken system, he decided to build a generation that could repair it.

Planting the Seeds of KEDI

In 2016, Pandya launched the Kids for the Environment Development Initiative (KEDI) at St Kabir School. Instead of lectures, children got their hands into the soil. Class 4 students began with farming, Class 5 explored insects, later moving to birds, trees, and water. Each step naturally revealed how ecosystems connect.

Learning was never about exams. Instead, students expressed knowledge through drawings, skits, songs, and even documentaries. One group even made a short film on how to bring sparrows back.

“Until 2023, there were no paper-pencil tests,” Pandya says. “The focus was on curiosity, not marks.”

Principals echo the impact. “One 70-minute session with Hitarth equals 100 hours of textbook learning,” says Lina Shajy of Tejas Vidyalaya.

From Classrooms to Mandis

Beyond farming, KEDI introduces children to the economics of agriculture. At the student-run KEDI Haat, children haggle like vendors, track mandi prices, and balance accounts before selling their produce.

Each year, students collectively sell over 3,500 kg of soil-grown vegetables and 2,000 kg of terrace-grown greens. At the Harvest Festival, the produce is cooked in a Sanjha Chullha (community kitchen), and every child contributes chapatis from home.

The results are visible beyond school walls. Parents began balcony gardens, children learned not to waste food, and even simple habits like pouring leftover water at tree roots took root.

Adapting, Growing, Spreading

When schools lacked space or time, Pandya innovated. Inspired by education reformer Sonam Wangchuk’s advice, he designed a three-month, hands-on module that fit into tighter schedules. By 2024, OneWorld School had adopted the model.

Soon, his expertise drew recognition from Gujarat’s Department of Science & Technology, Rajasthan’s SCERT, and DIET Vadodara, which invited him to train teachers.

A Passion that Became a Vision

For years, Pandya ran KEDI without financial gain. Today, his vision is expanding,to train teachers, empower communities, and blend subjects through experiential learning.

“The real challenge is breaking silos,” he says. “Math has art in it, and art has math. Children must see those connections.”

His students already do. “Amir ho ya gareeb, khana to sabhi khet se hi khate hai (Rich or poor, everyone eats from the farm),” says Swara, a Class 8 student.